Malcolm Kenter "Nonfiction"

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”

― Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

"Infrastructure makes society go. Superstructure makes society go smoothly (or bumpily)."

— Samuel R. Delaney, Times Square Red Times Square Blue

In cities like San Francisco, the encroachment of privatization and corporatization into urban spaces has eroded and profoundly transformed public infrastructure. Corporate offices are constructed with both the aesthetic and function of impenetrability, a barrier against the visible poverty that lines the urban landscape. Instead of using public buses and trains, tech conglomerates created semi-private transportation lines that use public bus stops as the entry point into a world that is not publicly accessible. Seamless rows of glass and steel tower over the city and private above-ground bridges function to physically separate the tech workers from the broader public. This aesthetic is in part built on the back of the technical progression that has transformed and invisibilized the physical instantiation of public infrastructure; phone lines, telephone poles are moved underground and into the walls of buildings.

Public utilities–electrical boxes, fire alarms, exhaust vents–are typically designed to be ignored, but have now become stubborn outsiders amid the smooth veneer tech industrial urbanization. Malcolm Kenter wants to preserve these disappearing elements of his native city through the reconstruction of defunct utility boxes, tubes, pipes, and other ephemera that literally used to make the city run. Many of these boxes and vessels Kenter is replicating have electrical wiring, communication lines, and gas lines within them that are integral to the actual operation of a city, thus they can not be bulldozed as easily as a facade or railway. They become a wart on the side of an otherwise seamless and humanless city view, and the final holdout of a demolished building or a defunct passageway. Many of the objects he replicates have been painted, scratched, bent, storing a human presence within their facade. These objects become remnants of the very last time a space was affected by a human presence–before the transition from sidewalk to building becomes a precise ninety degree angle, invulnerable and lifeless.

The minutiae of these boxes may seem insignificant, yet points to a time when not everything was made in the same factory with the same materials. A small shop might have produced the fire alarms for a SoMa street corner while in Nob Hill they were purchased from a mom and pop hardware store in the Marina. The uniformity of a city's most basic forms down to the last screw reflects the monoculture being created–where everything is interchangeable and has a place. Kenter’s work reminds us of the living, idiosyncratic, and deeply human urban history that cannot be so easily replaced.

-

Malcolm Kenter, Eagle Traffic Control, 2023

Malcolm Kenter, Eagle Traffic Control, 2023 -

Malcolm Kenter, BKF by KENTERCO, 2023

Malcolm Kenter, BKF by KENTERCO, 2023 -

Malcolm Kenter, Bryant Load Center, 2023

Malcolm Kenter, Bryant Load Center, 2023 -

Malcolm Kenter, DEPT OF ELECTRICITY by GAMEWELL, 2023

Malcolm Kenter, DEPT OF ELECTRICITY by GAMEWELL, 2023 -

Malcolm Kenter, Fire Alarm Box with Tublet, 2023

Malcolm Kenter, Fire Alarm Box with Tublet, 2023 -

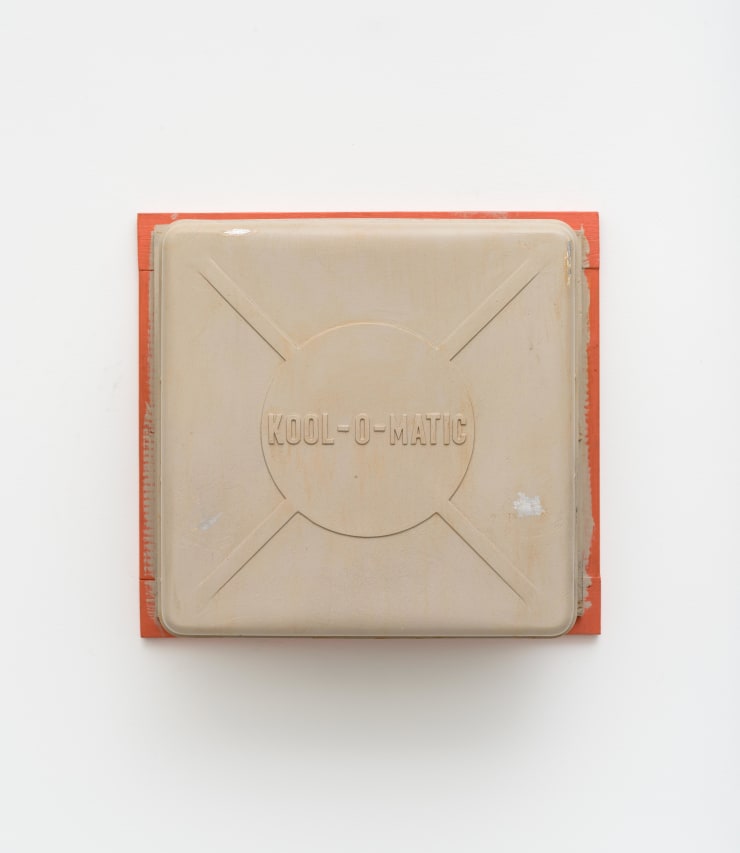

Malcolm Kenter, KOOL-O-MATIC, 2023

Malcolm Kenter, KOOL-O-MATIC, 2023 -

Malcolm Kenter, MERLITE, 2023

Malcolm Kenter, MERLITE, 2023 -

Malcolm Kenter, NUTONE WALL-PLUG, 2023

Malcolm Kenter, NUTONE WALL-PLUG, 2023 -

Malcolm Kenter, O.Z./GEDNEY by SG Inc., 2023

Malcolm Kenter, O.Z./GEDNEY by SG Inc., 2023 -

Malcolm Kenter, For Fire, 2023

Malcolm Kenter, For Fire, 2023