Nihura Montiel "Corporate Goddess" : New York

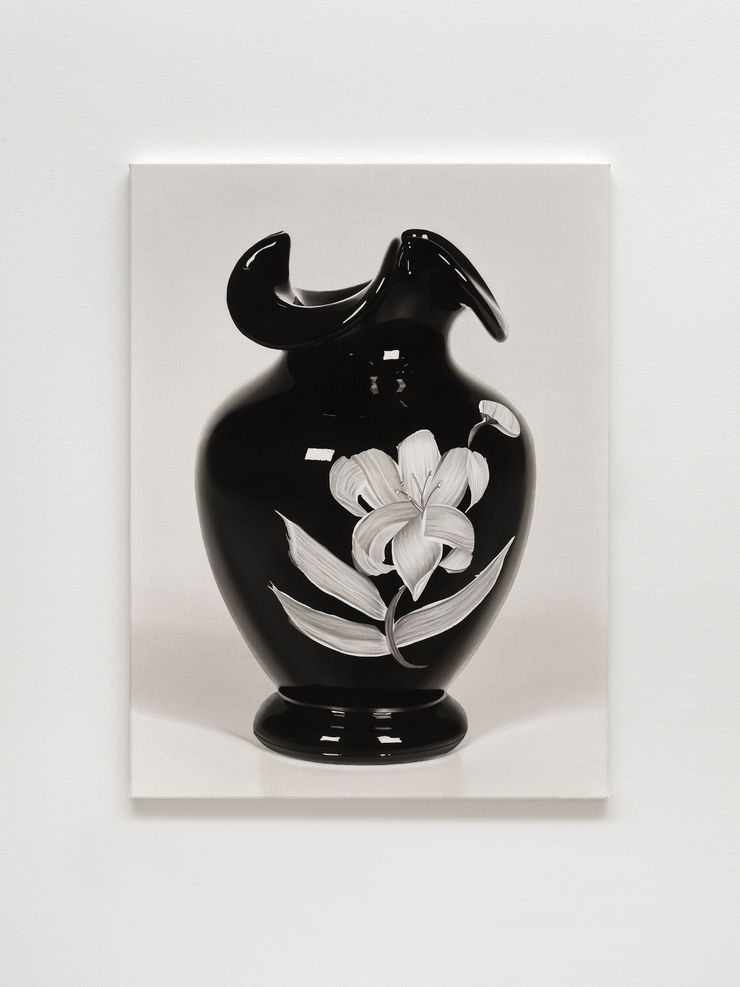

In Nihura Montiel’s studio—a former upholstery shop on an inconspicuous block of Pico Boulevard in Los Angeles—fluorescent track lights cast an even, bright glow over stainless steel tables; suede jewelry cases neatly line countertops, brimming with pyramids of loose charcoal; and bouquets of feathery makeup brushes fill jars, bristles shiny and taut. Each fixture has an air of meticulousness—an austere sanctuary for the seven grayscale canvases that hang from each wall, depicting a model boat, a bejeweled buddha, a rooster bronze, a cocktail shaker, a decorative mirror, a crystal cat, and a sculpture of the blindfolded goddess Fortuna. Seated on a spotless cream sofa overlooking her work station, Montiel stacks piles of reference materials across a coffee table for perusing as she embarks on a discussion of her latest series: Corporate Goddess.

-Anna Bane

AB: You selected these objects from various sources ranging from decorative art books to auction lots. Was there a vision that directed your gravitation toward these particular subjects?

NM: When I imagine the universe these objects occupy, I picture them scattered across the executive office of a corporate high-rise. The type of indulgent decor that might be found in Michael Douglas’ study in the 1997 film The Game. Each ornament is laced with quiet spectacle—clichés of a risk-and-reward way of life. I invite my audience to settle into this scene and observe the experiences, emotions, and associations they conjure. Posed on neutral backdrops, I create an opportunity for us all to behold the same image, yet paint different mental pictures and draw unique assumptions about class and status codes. In my practice, the subject is explicitly the object—items that reflect our projections back to us in their polished surfaces.

AB: Without insisting on a specific reading, can you share the origin of some of these talismanic tchotchkes?

NM: Cartier Buddha is based on a jade figure encrusted with precious stones designed by Fabergé, reproduced by Cartier, and auctioned at Bonhams—an exclusive emblem of non-attachment. Cock, inspired by El Gallo—the nickname of my family’s patriarch—is a mascot of our feisty, argumentative nature that recalls phrases like “the early bird gets the worm” and “rule the roost.” Awaiting Reprieve is based on an Art Nouveau mirror named “The First Cuckoo”—a tech-era homage to the myth of Narcissus in which a maiden peers into the pane and, in place of her reflection, confronts a void. In each work, there is space for the literal and the teasing, testy, or tongue-in-cheek. I want to coax the paradoxical nature out of coveted, inanimate objects.

AB: Whether depicting a vessel or a void, your surface textures are the mesmerizing result of what you call “dry” painting. Why do you feel charcoal is the ideal material to achieve this effect?

NM: For me, charcoal is the only medium that conducts alchemy—imbuing dense, rigid elements of glass, steel, and stone with sensations of velvet, satin, and gloss. I want someone to feel the aura of the work and walk away wondering how it was made. Just as I like that my seemingly internet-rabbit-hole references actually come from physical books I check out from the library, I also like that I create airbrushed, digitally-rendered effects by manually applying pigment with contour makeup brushes. Charcoal is a high-stakes medium, and in each successive series, I challenge myself to image objects that are progressively more intricate and demand even greater reserves of mental fitness and meditative focus. With each canvas, I get one shot. There is no room for error. These works are the result of all-or-nothing executive functioning.

AB: Your imperceptible hand is exalted by your analog approach. Can you describe your process and technique?

NM: First, I take charcoal sticks and crush them into a fine powder using a coffee grinder. Then, I cover the canvas with a masking sheet and, in pencil, draw a grid, sketch an outline, and cut out the negative—nothing touches the canvas but charcoal. Once I remove the mask from the background, I lay the canvas on the ground, get down on my knees, and pour even layers of powdered charcoal over the entire image plane, buffing out up to ten layers of charcoal with a large contour brush until it is perfectly smooth. After, I may take a chamois cloth and gently smack the surface to give the backdrop that 1990s marbled effect. Setting the powder with a workable fixative, from there it’s all brushing, layering, and blending. I use only pure black, six shades of gray, and gessoed canvas.

AB: Among these reliquaries of capital, Fortuna is the high priestess. With her blindfold in your hand, how do you determine what to channel and to challenge within her cascading cornucopia?

NM: In exploring how aspirational selves are expressed through materialism, I am intrigued by the way she dispenses fortune “impartially.” We are living in a time when fantasy is trending in art and culture, and we are constantly being spoon-fed other people’s seductive delusions—encouraged to ferociously devour and carelessly discard them. My work won’t coddle you. It won’t leave you full. I want you to pull up a chair next to me in the executive office, and together we can take in a physical world, close our eyes, and descend into our own personal visions and biases—good and bad. This mental bank has no withdrawal limit, but I won’t do the work for you. When you leave the show, I want these images to linger on the mantle of your mind’s eye.